Fanny Chabrol, Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale (Inserm)

The five strains of viral hepatitis (A, B, C, D and E) affect 400 million people around the world. Hepatitis B and C are the most deadly; these infections are blood borne, transmitted mainly through unsafe medical practices or injection drug use.

International awareness has grown following activist mobilisation denouncing the exorbitant prices of new drugs that can cure hepatitis C such as Solvadi, priced at US$1,000 a pill.

Viral hepatitis is a global epidemic with distinct regional patterns. In Europe, hepatitis C is mostly associated with injecting drugs but on the African continent, it is a generalised epidemic and a major public health issue.

In both 2010 and 2014, the World Health Organisation (WHO) called for action on the diseases and has since produced guidelines for testing for hepatitis B and C.

The case of viral hepatitis sheds light on the key challenges faced by health systems in Africa in relation to the prevention of infection, barriers to accessing care and treatments and social and economic equity.

A deadly epidemic

It is estimated that 100 million people are affected by chronic hepatitis B in Africa, most of whom don’t know they have the infection; 19 million adults have hepatitis C.

Despite a lack of accurate epidemiological data at national levels, various estimations put hepatitis B prevalence at around 8-10% of the population in many countries. It is a generalised epidemic, not confined to specific segments of the population or high-risk groups.

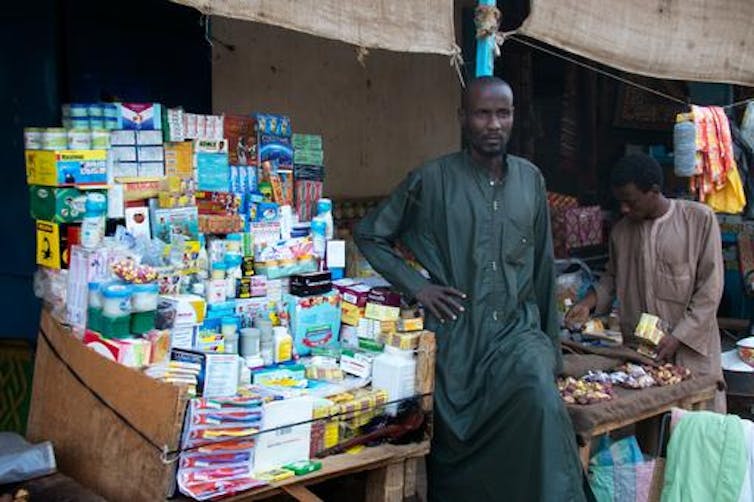

This epidemic is even more worrying when we consider how hard it is to get treated – only 1% of chronic carriers can access treatment. When patients test positive for hepatitis they must undergo a series of biological and molecular tests that are, at the moment, unacceptably expensive in Africa.

It costs between €200 and €400 to have a complete pre-therapeutic assessment for hepatitis B or C in Cameroon and around €210 for an assessment for hepatitis B in Burkina-Faso.

After these tests, very few patients make it to the antiretroviral treatments. which are available for HIV patients but not for those affected by hepatitis B. In the case of hepatitis C, a single injection of pegylated interferon can cost as much as €230 in Côte d’Ivoire or Cameroon, and patients need 46 injections minimum.

If a hepatitis patient cannot access regular treatment, they end up hospitalised, affecting entire families both emotionally and financially. The people who die young of the diseases represent the workforce in many countries. As in the early years of AIDS, the shape of Africa’s future is affected by these infections.

A history of neglect

And just as the AIDS epidemic embodied colonial violence and weak health systems, so does viral hepatitis.

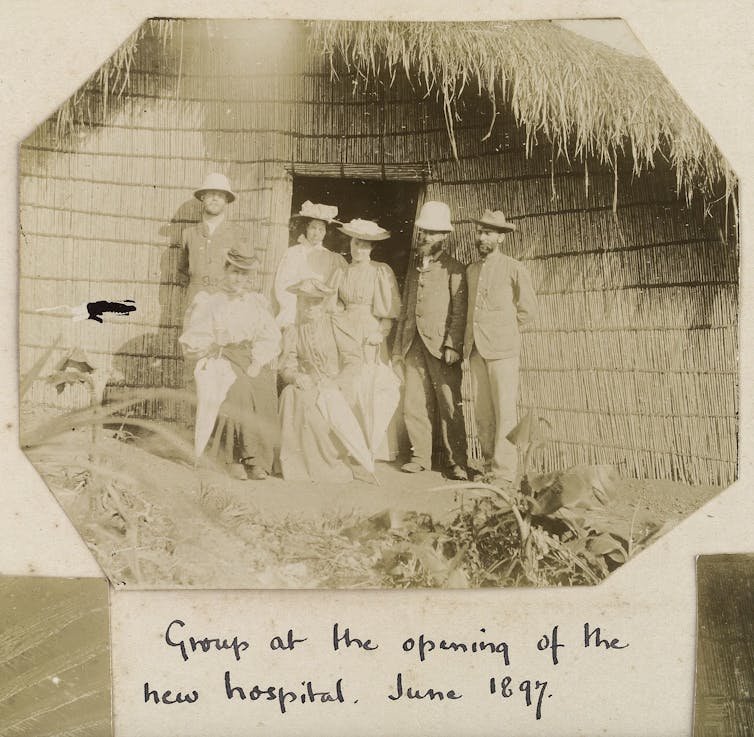

In Cameroon, the hepatitis C virus was transmitted through colonial medical campaigns in the late 1950s to 1960s. In Ebolowa, it is associated with intravenous treatment of malaria that today’s older people received when they were young; hepatitis C therefore affects more than 50% of people older than 50 in certain regions.

Transmission of hepatitis C might not be acute today, but certain medical procedures do carry the risk of infection. In Cameroon, those who undergo repeated blood transfusions are at greater risk of contracting HCV, just as health workers, exposed in the workplace.

Viral hepatitis also sheds light on global healthcare priorities. The hepatitis B vaccines arrived late to the African continent: though the extent of hepatitis B and liver cancer were known in the late 1970s in Senegal and stimulated the development of a vaccine, once manufactured this vaccine was not made accessible in Africa until mid-1990s. Even today, populations are not fully covered by vaccination.

In the 1980s the HIV epidemic obscured the extent of hepatitis. Today, the free antiretroviral drugs provided through the support of Global Fund against HIV, TB and malaria are perceived as unfair by many of those affected by hepatitis.

People’s science

In the fight against hepatitis, many lessons can be drawn from HIV, as well as from the recent Ebola outbreak.

Massive international interventions cannot just target access to drugs and biomedical interventions. Chances of surviving Ebola were considerably increased when patients could access basic measures, including intensive care and rehydration.

And instead of trying to change people’s behaviour, history shows it is wiser to understand the social, economic and political context of epidemics and to trust local knowledge and experience. In his recent book on Ebola, anthropologist Paul Richards asserts that the epidemic ended not just because of international support, but also thanks to community work, even despite the lack of effective treatment.

Communities responded, and they produced their own science of the disease. They mobilised techniques to protect themselves, for instance by using plastic bags or other materials while attending to their sick loved ones.

Today, in places like Cameroon, many physicians, patients and families have similarly developed ways to cope with hepatitis, jaundice or liver pathologies. Their insight and experience should be at the centre of future policies.

Many professionals deplore the lack of universal protection from hepatitis transmission and the risk of infection in hospitals is high. Health workers are not immunised correctly, and they lack critical equipment such as gloves and sterilising material.

Another efficient way to prevent transmission is to vaccinate for hepatitis at birth instead of starting at six weeks.

There is also an urgent need to address pain management and palliative care as the complications of hepatitis (liver cancer and cirrhosis) can be very debilitating and inhumane experiences, often leading to death.

Urgent action

Across the African continent, hepatitis does not today receive the same kind of attention from NGOs and civil society as HIV did in the 2000s.

But other forms of mobilisation are emerging among clinicians, as national professional associations combine scientific and medical work and advocate to their respective governments for sustained pan-African collaboration.

Clinicians in Africa and in Europe are also joining forces through scientific and medical cooperation and are calling for action to fight these unacceptable global inequalities. Their insights should be combined with strong social support for patients and their families.

The viral hepatitis response also requires urgent infrastructure interventions to ensure access to clean water, hospital hygiene and blood safety.

The WHO Regional Committee for Africa promotes a public health approach that includes vaccination at birth, integration of testing services and linkage to care.

If making drugs available is a priority, it is also imperative to avoid catastrophic health expenses and include diagnostic tests, treatments and follow-up tests in national projects for universal health coverage.

Fanny Chabrol, Postdoctoral fellow in Global health, Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale (Inserm)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Warning: file_get_contents(https://plusone.google.com/_/+1/fastbutton?url=https%3A%2F%2Fkigalihealth.com%2Fhow-hepatitis-became-a-hidden-epidemic-in-africa%2F): failed to open stream: HTTP request failed! HTTP/1.0 404 Not Found in /home/kigal4health/public_html/wp-content/themes/goodnews5/goodnews5/framework/functions/posts_share.php on line 151